FAU Historian Traces How U.S. Nursing Homes Evolved into Big Business

Postcard showing a typical Americana Nursing Center design, as employed in the facility that opened in Normal, Illinois in 1962 (author’s private collection).

Study Snapshot: In a new article, historian Willa Granger, Ph.D., explores how a little-known Illinois company, the Americana Corporation, helped shape the modern nursing home in postwar America. During the 1960s, Americana developed a replicable model of suburban, hospital-adjacent facilities that blended real estate, institutional medicine and franchising – transforming eldercare into a standardized, corporate system tied to federal policy and funding.

Granger’s research reveals how architecture was central to this shift, not just housing older adults but creating an entire system of care. By examining the physical and institutional design of Americana’s homes, she uncovers how midcentury ideals around aging, medicine and profit became embedded in the built environment – a legacy that continues to define long-term care today.

In postwar America, as suburbs spread and federal social welfare programs expanded, one underexamined building type quietly became a fixture of the American health care landscape: the nursing home.

In a new article published in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, historian Willa Granger, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the School of Architecture within Florida Atlantic University’s Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters, examines how a little-known company from midcentury Illinois helped lay the groundwork for the modern nursing home industry in the United States.

Granger’s research centers on the Americana Corporation, a for-profit eldercare chain that pioneered a replicable model of suburban, hospital-adjacent nursing homes during the 1960s – ultimately reshaping not only how older adults are cared for, but where and by whom.

Through meticulous archival research, Granger draws from internal business records, marketing materials, and federal policy documents to show how nursing homes evolved from small, local operations – often run out of converted houses – into standardized, medically regulated institutions tied to federal funding and corporate expansion.

Granger’s article is one of the first comprehensive architectural histories of the nursing home in the U.S. By placing this overlooked building type at the center of debates about health care, policy and design, she opens new questions about how architecture has participated in shaping social institutions – not only reflecting cultural attitudes toward aging but actively producing them.

“This is not just a story about nursing homes. It is a story about how buildings mediate care, how federal policy influences physical space, and how the structure of eldercare became a mirror of midcentury American life – its promises, its anxieties and its enduring contradictions,” said Granger.

Americana wasn’t just building nursing homes. It was building a system – one that merged health care with real estate, design and franchising. In doing so, it helped redefine what eldercare looked like, both physically and institutionally.

Founded in 1960, Americana was conceived to bridge the growing gap “between hospital and the private home,” according to its early marketing materials. Americana’s facilities were strategically sited near regional hospitals in growing suburban and rural markets. Its facilities were purpose-built, single-story structures styled in familiar neocolonial architecture – with brick facades, white porticos and decorative shutters – but internally organized according to clinical, hospital-style layouts. Americana’s leaders borrowed tactics from the booming motel industry, blending real estate development, standardization and institutional medicine to build nursing homes across the Midwest that felt like home but functioned like hospitals.

By 1969, the company had developed more than 30 locations across nine states. Its success was driven not only by design and branding, but by a unique moment in U.S. policy. Granger’s article demonstrates how federal programs like the Hill-Burton Act, Social Security, and especially Medicare, helped incentivize and normalize this new model of care. The very programs meant to support aging Americans also helped consolidate eldercare into a professionalized, increasingly privatized industry.

“Americana shows how architecture was used not just to house people, but to create an entire system of care – one shaped by regulation, profit and a vision of aging that was both medicalized and marketable,” said Granger.

By contrasting Americana’s approach with earlier operators like Leonard Tilkin – a Chicago-area businessman infamous for running understaffed, substandard facilities out of converted historic homes – Granger reveals how architecture became a key player in the moral and economic politics of eldercare. While Americana met newly imposed safety and licensing standards, it also signaled a broader shift toward corporate models of caregiving that prioritized scale, replication and compliance over community and personal connection.

Granger’s study raises urgent questions about the legacy of this shift and its continued relevance today.

“As the U.S. faces a rapidly aging population and mounting pressures on long-term care, the origins of the modern nursing home reveal how deeply our built environments reflect the values – and blind spots – of their time,” said Granger. “History reminds us that decisions about architecture, policy and profit are never neutral; they shape the everyday lives of vulnerable people. Understanding where these systems came from is essential if we hope to imagine and build something better.”

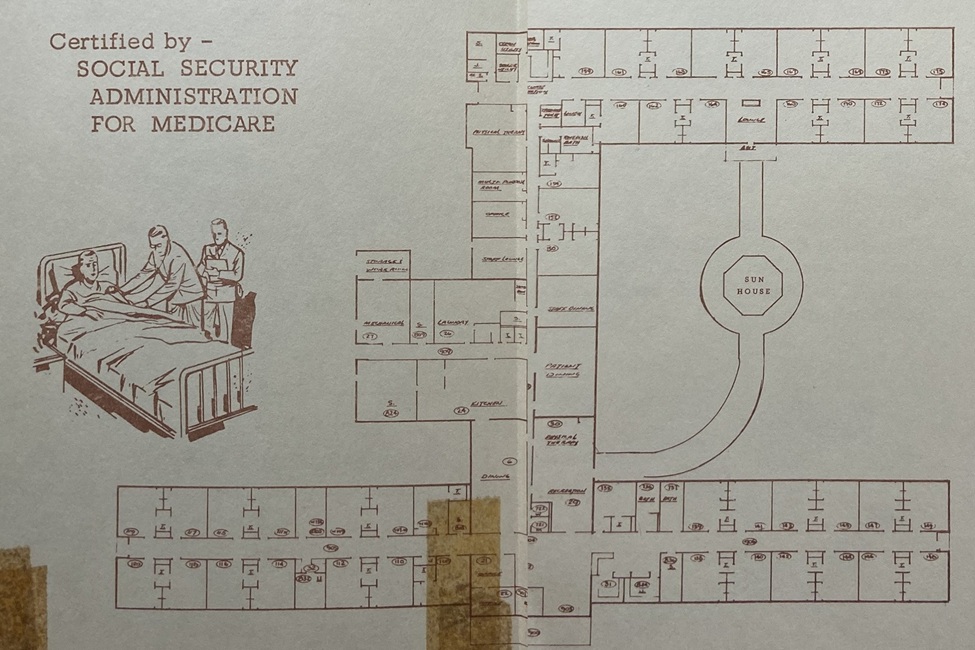

Advertisement showing the plan of Florence Baltz’s Washington Nursing Center in Illinois, 1967 (Washington, Illinois Historical Society).

Postcard showing the later Americana Nursing Center design as employed in Urbana, Illinois in 1967 (author’s private collection).

-FAU-

Latest Research

- Where a Child Lives - Not Just Diet - Raises Type 2 Diabetes RiskFAU researchers found poor walkability, litter, and reliance on assistance programs are strongly linked to type 2 diabetes risk in young children, based on a large nationwide study.

- FAU BEPI: Economic Strain Hits Hispanic Households Hard in 3rd QuarterHispanic consumer confidence dropped in the third quarter of the year as uncertainty and increased prices placed added pressure on their budgets, according to a poll from Florida Atlantic University's BEPI.

- FAU's Queen Conch Lab Receives Prestigious International AwardFAU Harbor Branch researchers have received the 2025 Responsible Seafood Innovation Award in Aquaculture from the Global Seafood Alliance for its Queen Conch Lab's pioneering work in sustainable aquaculture.

- After Cancer: Study Explores Caring-Healing Modalities for SurvivorsResearch from FAU's Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing highlights how caring-healing methods like mindfulness can ease distress and build resilience in cancer survivors.

- FAU Researchers 'Zoom' in for an Ultra-Magnified Peek at Shark SkinWhat gives shark skin its toughness and sleek glide? Tiny, tooth-like denticles. Researchers used electron microscopy to reveal how these structures shift with age, sex, and function in bonnethead sharks.

- FAU Lands $3M Federal Grant to Prevent Substance Use in At-risk Youth"Rising Strong" will support more than 3,000 South Florida youth with trauma-informed, evidence-based prevention, empowering vulnerable populations to build resilience and choose substance-free futures.